The Rana Plaza factory was eight stories high, a monolith of grey concrete that collapsed in on itself in a scene that resembled the chaos and tragedy of an earthquake or a war zone. Over 2,500 of the factory workers were injured and 1,135 were killed.

80% of the workers caught inside Rana Plaza that day were women. They were mostly young, 18–20 years old, and forced by poverty to work in the factory for around 22 cents an hour.

This is a picture painted across garment factories around the world that employ an exploitative economic model driven off the back of women’s underpaid labour. And yet, as quickly as the chilling story of the Rana Plaza disaster hit the global news, it was all but forgotten.

Rana Plaza collapse, Bangladesh.

Instead, the eyes of the Global North were immediately drawn to the clothing labels that lay amongst the rubble. The labels revealed that Rana Plaza serviced an array of multi-billion dollar brands, among them, JC Penney, Benneton, Mango and Primark.

These labels brought the Rana Plaza disaster right here into our wardrobes.

News headlines called it a “wake-up call for the fashion industry” and demanded a “clean up of global sweatshops”. Many Australians were shocked. The logos we had filled our closets with were frauds; their sweatshops built on exploitation, poverty and death.

It has been four years since the Rana Plaza disaster. Predictably, the outrage about appalling working conditions and slave-like labour proved fickle and our shopping habits barely changed. The Australian fashion industry continues to rake in an estimated annual revenue of $19 billion. The Australian taste for fast fashion is picking up speed, not slowing down.

Not much has changed either in terms of the price women garment workers pay for making our clothes. Around the world, three quarters of the estimated 60-75 million people working in the textile, clothing and footwear industries, are women and girls. Reports of garment worker deaths have continued to surface from around the globe and, so too, have stories of garment workers sacked or harassed for standing up and demanding their human rights.

Yet the plight of women garment workers has not seen the rise of a consumer movement with anything like the zeal of all things ‘eco-friendly’ and ‘green’. A Google search of feminist clothing does not result in a discussion on women garment workers and their rights, but clothes branded with feminist slogans and little information as to how they were made.

It’s a story as old as time. In 1911, the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire in New York killed 146 women, many of them jumping from the flames to their deaths. They were mostly young Jewish and Italian women, migrant workers earning a paltry $15 a week.

What differed in 1911, was that the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire was understood immediately as a feminist issue of immense moral urgency.

Speaking at the Metropolitan Opera House eight days after the fire, Rose Schneiderman, a Jewish-American feminist and prominent labour union leader, channelled her grief into a momentous speech, excoriating a society that had allowed the Triangle Shirtwaist fire to happen.

“This is not the first time girls have been burned alive in the city,” she said. “Every week I must learn of the untimely death of one of my sister workers. Every year thousands of us are maimed.”

The following year, Schneiderman would utter one of the most famous phrases in the history of Western women’s movements: “The worker must have bread, but she must have roses, too. Help, you women of privilege, give her the ballot to fight with.” With these 23 words, Schneiderman called for a solidarity that recognised and defied class lines. Her audience was made to understand the plight of working class women as deserving of, not just the most basic labour rights, but conditions that allowed for dignity and a meaningful life, like those roses women of privilege enjoyed so freely. It was a statement that drew a straight line connecting the conditions – and the humanity – of the working class and the wealthy.

Today, that solidarity must also stretch across global borders and it must recognise that, whether we like it or not, everything we wear is political. Too often, Australians wear clothes that connect us to severe human rights violations of women garment workers in low-income countries. Though it may be tempting to consider ourselves beholden to the leviathan that is the global fashion industry or capitalism, our dollars are its working parts, the breath and the blood that keep it moving.

The good news is that this means we also have the power, and the responsibility, to shut down the abusive fast-fashion industry. It also means we have the power to build a new system designed for women, by women.

This is the vision that prompted ActionAid Australia to connect The Fabric Social, an ethical Australian fashion label, with MBoutik, a collective of women in Myanmar producing fashion-forward and environmentally-friendly clothing. The women of MBoutik live in Myanmar’s Dryzone, where the impacts of climate change are hitting women and their communities hard, creating severe food and economic insecurity. Armed with their ‘Flying Man’ sewing machines and entrepreneurial determination, the women of MBoutik are using fashion to create a better, more secure future for themselves, and their communities.

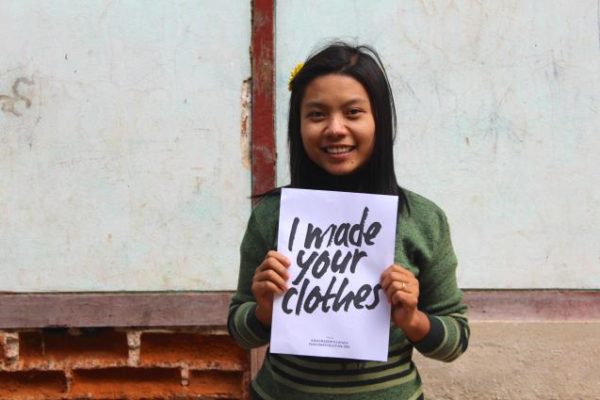

Hnin Nu Wai, a woman producer from MBoutik.

Maw Maw Lin, Nyo Nyo San, Yin Yin Ale, Moe Moe, Zar Zar and Hnin Nu Wai – these are the women of MBoutik. They are skilled clothes producers and they are also women who love motorbikes, singing, jewellery-making, sharing funny stories about their boyfriends, and who dream of their children becoming doctors and community leaders. MBoutik offers each of these women a fair wage, dignified working conditions and the right to organise and voice their demands. This is what a feminist supply chain looks like and this is what we should demand from every brand we buy.

The ruthless exploitation of women garment workers, so often left faceless and nameless, is among the most disgraceful symptoms of globalised capitalism and it has continued largely unchallenged since the first days of industrialisation. It will take more than ethical consumption to bring about global gender equality and justice. But taking your dollars out of the pockets of a tyrannical fashion industry and investing them in a system that cares, that can tell you its employees names and their stories, that has human rights at its core, is an important contribution – and our responsibility as consumers and feminists.

———

The innovative business partnership, coordinated by ActionAid Australia through funding from DFAT’s new Business Partnerships Platform, is supporting women in Myanmar to realise their economic independence and full human rights.